In the past decade the Lake Chad Region, including parts of Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria, saw multiple crises and conflicts, with climate change intensifying existing conflict dynamics and creating new risks. Communities in the region are vulnerable to both the profound impacts of climate change and the ongoing conflict. In a project supported by the UNDP, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the German Federal Foreign Office, PSI Consortium member adelphi took the lead on the spotlight region Lake Chad, resulting in a report that addresses Climate and Fragility risks in the region. After presenting and discussing the findings during a special session at the Planetary Security Conference 2019 the full report is now published and available for download.

[The following article authored by Natalie Sauer originally appeared on climatechangenews.com]

Satellite analysis shows ‘vanishing’ lake has grown since 1990s, but climate instability is driving communities into the arms of Boko Haram and Islamic State. Climate change is aggravating conflict around Lake Chad, but not in the way experts once thought, according to new research.

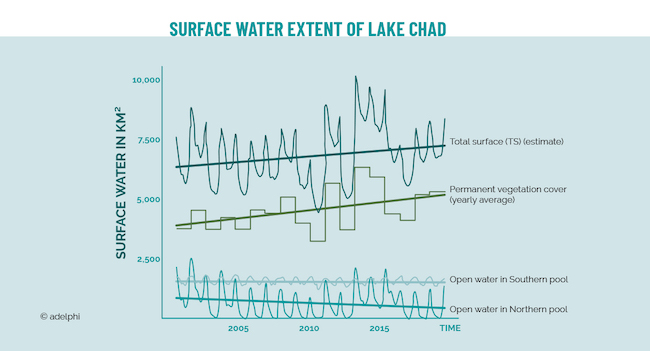

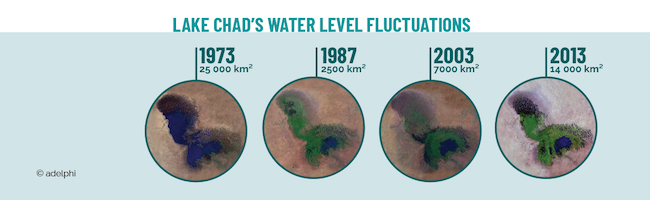

Berlin-based think tank adelphi debunked the widely held idea that the lake is currently shrinking. While severe droughts in the 1970s and 80s shrunk the lake from a high-point of 25,000 sq km to 2,000 sq km in the 1990s, it has since grown to 14,000 sq km and remained relatively stable in the past two decades.

The findings draw on new analysis of 20 years of satellite imagery and long-term hydrological data from the Lake Chad basin, including ground measurements.

Previous satellite images underestimated the amount of water in the lake, in part because of the growth of plants that stood in the water, lead author Janani Vivekananda told Climate Home News.

“Different satellites give you different kind of information, and have limitations,” Vivekananda said. “Very often when you’re looking down from 30,000 feet, you miss information such as the water that’s under vegetation cover.” Researchers looked at infrared images to probe into the volume of water, she said.

The conflict and humanitarian crisis driven by the “shrinking” lake is often cited as a textbook example of climate change affecting security. But warming remains an important factor, according to the study, which also drew on 200 interviews with local communities.

Rising temperatures – up to one and a half times faster than the global average – and increasingly erratic rain patterns have created food insecurity, ultimately pushing communities into the arms of terrorist groups like Boko Haram or Islamic State West Africa Province.

“The unpredictability of rains means that people are just giving up,” Vivekananda said. “After the third or fourth failed harvest, not knowing when to switch from fishing to farming, the offer of a livelihood of food every day and business loans becomes more attractive.”

Lake Chad, which straddles Nigeria, Niger, Chad and Cameroon, is home to 17.4 million people. Around 10.7 million people require humanitarian assistance, with 5 million suffering from food insecurity. Some 2.5 million people have fled their homes.

Since 2009, violence in northeast Nigeria has boiled over into neighbouring Cameroon, Chad and Niger. A range of factors were feeding the region’s instability. Successive economic crises, divisive reforms and weak governance in the region, coupled with rising inequality and dismay at corruption among the ruling elite have created a hotbed for tensions.

Climate change, the report found, both worsened the conditions at the root of conflicts, and undermined communities’ ability to deal with them.

Where elders once used to serve as mediators in disputes, recurring war and heat waves have shredded the social fabric to such a point that this is no longer possible.

In the past, “two parties might go to an elder and agree to some kind of restitution,” Vivekananda said. “They might make amends by giving them a share of their next harvest. But these don’t work any more, because the influx of people – because of the conflicts and displacement – make it a very transient society.”

Competition over natural resources has also flared, as fertile land becomes scarcer.

Authors urged governments to incorporate climate resilience into their strategy for peacebuilding in the region. Among an array of solutions, the report suggested policymakers provide better hydrological information to communities so that they could plan around rain-falls. Also essential were investments into long-term infrastructure and better resource management.

On the other hand, heavy-handed military responses, such as blanket bans to certain areas in an attempt to root out terrorist groups, have failed the region, provoking further displacement.

Lake Chad has long been the poster child of climate security. In 2015, Barack Obama urged military officials to “understand climate change did not cause the conflicts we see around the world. Yet, what we also know is that severe drought helped to create the instability in Nigeria that was exploited by the terrorist group Boko Haram.”

The United Nations Security Council is increasingly recognising the role of climate change in exacerbating conflict, particularly in West Africa and the Sahel region, where Lake Chad lies.

At a meeting of the Security Council in January, France and the UK were joined by Germany, Peru, Poland and Belgium in a call for a system to help them respond to climate security threats. France also called for the UN secretary general to deliver an annual report to the security council on the issue. Only Russia explicitly opposed the development of new UN capabilities.