The following is an excerpt of the original article authored by Marcus King and Emily Hardy.

This briefer highlights the core elements of water weaponization and assess its practice in the Russia-Ukraine war to date.

Water Weaponization and the Russia-Ukraine War

The Russian invasion of Ukraine illustrates that water weaponization continues to occur at the state level. Since the 2022 invasion, numerous instances of water contamination, destruction of ecosystem services, and targeting of water infrastructure have occurred – limiting water availability that is essential for basic survival, as well as Ukrainian agriculture and energy systems. Given that Ukraine is often considered the breadbasket of Europe, due to the importance of its exports for regional and global markets, Russian water weaponization in the conflict has driven significant food security consequences both within the country and globally – particularly in the Middle East and North Africa. Disrupted water infrastructure that is critically important for nuclear energy systems has also driven significant fears of environmental disasters that could have global consequences. Lastly, while Russia remains the primary aggressor in the conflict and the main facilitator of water weaponization, Ukraine also employed similar tactics of water denial on the Crimea peninsula following Russia’s illegal annexation, and has occasionally used water weaponization in other arenas of its conflict with Russia.

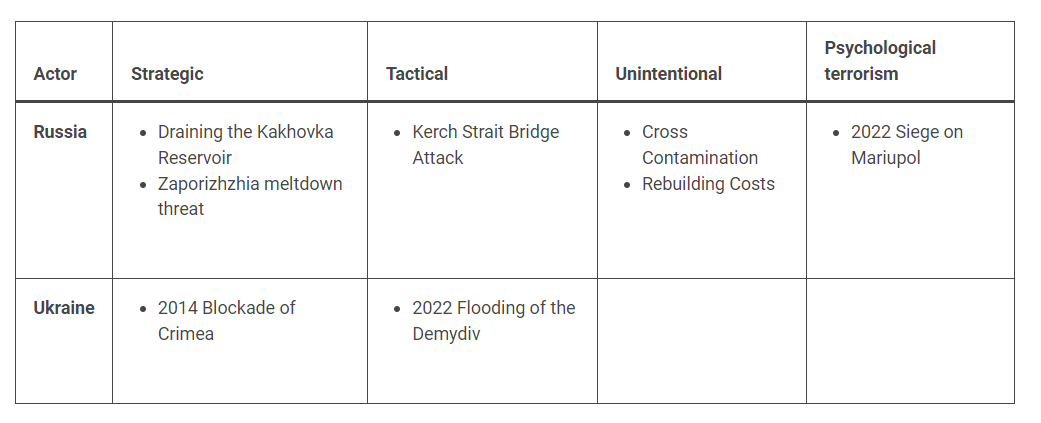

Key instances of water weaponization in the Russia-Ukraine conflict are discussed and mapped below, as per the aforementioned six-category matrix.

Table: Key Weaponization Incidents in Ukraine

Strategic Weaponization: The use of water to destroy large or important areas, targets, populations, or infrastructure

Connected to the Dnipro river, the Kakhovka Reservoir in southern Ukraine provides critical water for local populations and crop production. Perhaps more importantly, however, is the Kakhovka Reservoir’s role in cooling the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power station—Europe’s largest nuclear power plant. According to Hydroweb, the water level in the reservoir was the lowest it had been in over three decades, hitting 14.1 meters on February 6, 2023. Experts fear that the plant will be endangered if the water level dips below 13.2 meters. In late 2022, Russia began deliberately draining the Kakhovka reservoir, possibly to hinder Ukrainian agricultural production or troop movements, which could induce a nuclear meltdown with catastrophic health implications to surrounding populations, animals and ecosystems. Fear of a meltdown was so significant that UN observers recently visited the plant in March to assess these security vulnerabilities first hand.

The Nova Kakhovka Dam is another focal point of strategic weaponization. Both Ukraine and Russia have accused each other of planning to breach the dam using explosives. This act would flood much of the area downstream and cause major destruction to both civilian infrastructure and the ecosystem around the Ukrainian region of Kherson. Maxar satellite imagery found new damage to the dam following the Russian retreat from Kherson, but, at the time of writing, it has not been destroyed.

The primary example of Ukrainian strategic water weaponization occurred in 2014 prior to the current stage of the conflict, when Ukraine constructed a dam along the North Crimean Canal. This essentially eliminated all water access to the Russian-controlled Crimean Peninsula and diverted water to Ukraine’s Kherson region. This action was designed both to punish Russian aggression and compel a Russian retreat– a tactic that was clearly unsuccessful. Upon the invasion, Russia destroyed the dam in early 2022 to restore the Northern Crimea Canal water flow.

Tactical Weaponization: The use of water against targets of strictly military value within the battlespace

Tactical water weaponization has also been employed by Russia throughout the war. In October 2022, Russia launched 50 missiles on civilian infrastructure in Kyiv as an intrinsic part of its invasion plan. This attack left 40% of residents without access to water and 270,000 apartments without electricity. The inability to access clean drinking water increases susceptibility to water-borne illnesses and disease. Furthermore, attacks on the electrical grid disrupt civilian sanitation, risking disease outbreaks. Russian attacks on civilian water infrastructure have likely facilitated the spread of highly pathogenic diseases forcing people to live in unsanitary conditions without observing COVID-19 prevention measures.

In another incident from the battlefield in November 2022, retreating Russian forces from the city of Kherson detonated explosives on the Antonovsky Bridge. This tactical decision severed the primary crossing into Kherson, which made it challenging for Ukrainians to pursue Russians across the Dnipro river. Through eliminating the bridge, Russian forces capitalized on the new geographic environment to impede a Ukrainian advance. The Dnipro river serves as a natural barrier to troop and machinery mobility. As often happens when the water weapon is wielded, this action was a double-edged sword. While it made a Ukrainian advance nearly impossible, the bridge’s destruction also means that it is more challenging for Russians to successfully return to Kherson.

On the Ukrainian side, Ukraine was desperate to slow Russian advancement to Kyiv early in Russia’s invasion. In order to disrupt troop mobility, Ukraine intentionally released water into the Demydiv region, causing massive damage to residential and agricultural land. However, the act inhibited the Russian advance to the Ukrainian capital and gave the country time to prepare and rearm. This tactic funneled Russian forces into narrow pathways and forced tanks to different terrain–flooded bogs are impossible to traverse with heavy machinery.

Unintentional Weaponization: Attempted water weaponization causes collateral damage to the environment or its human component

It is possible that Russia’s deliberate destruction of Ukrainian land and infrastructure will come back to haunt it, especially if they intend to incorporate and administer captured territory. Russia’s invasion has devastated Ukrainian forests, farmland, and national parks, leaving an estimated 48 billion euros worth of damage. According to the Ukrainian government the cost to water resources alone is $1.6 billion, severely limiting access to the population, including in areas Russia currently controls and intends to administer.

Instrument of Psychological Terror: The use of the threat of denial of access or purposeful contamination of the water supply to create fear among noncombatants

Russia has also denied access to water to civilian populations as an instrument of terror designed to compel noncombatants to surrender. This strategy was evident in Mariupol where “soldiers shut off local water supply as part of a brutal siege on the city, leaving the trapped population without access to safe drinking water or sanitation.” Since May of 2022, Mariupol has remained under Russian control. In April 2022, Russian forces seized the southern coastal city of Mykolaiv, and satellite imagery revealed that they deliberately destroyed the water pipeline to the city during their occupation. When Ukrainian forces regained control of the city, residents were forced to queue in the street to collect clean drinking water. Residents had access to what is known as “technical water” in their homes, but it was polluted and could not be used for drinking or cooking. The queues were and continue to be dangerous and frightening, as the city remains close to the front line and is often shelled. This contributes to the psychological toll of restricted water access.

Conclusion

The Russia-Ukraine War is the one of the latest examples of water weaponization involving state actors, and it’s not likely to go away any time soon. The best ways to make states more resilient to water insecurity, and thus more resilient to attempts at water weaponization, is to both invest in infrastructure that is adaptive to climate change and other stressors–such as in future post-conflict reconstruction in Ukraine–and build out international legal systems to better regulate and disincentivize the abuse of water resources for political and military aims.

This is an excerpt from the briefer authored by Marcus King and Emily Hardy, and has been originally published by Council on Strategic Risks. Click here to read the full article.